Important update from TheSchoolRun

For the past 13 years, TheSchoolRun has been run by a small team of mums working from home, dedicated to providing quality educational resources to primary school parents. Unfortunately, rising supplier costs and falling revenue have made it impossible for us to continue operating, and we’ve had to make the difficult decision to close. The good news: We’ve arranged for another educational provider to take over many of our resources. These will be hosted on a new portal, where the content will be updated and expanded to support your child’s learning.

What this means for subscribers:

- Your subscription is still active, and for now, you can keep using the website as normal — just log in with your usual details to access all our articles and resources*.

- In a few months, all resources will move to the new portal. You’ll continue to have access there until your subscription ends. We’ll send you full details nearer the time.

- As a thank you for your support, we’ll also be sending you 16 primary school eBooks (worth £108.84) to download and keep.

A few changes to be aware of:

- The Learning Journey weekly email has ended, but your child’s plan will still be updated on your dashboard each Monday. Just log in to see the recommended worksheets.

- The 11+ weekly emails have now ended. We sent you all the remaining emails in the series at the end of March — please check your inbox (and spam folder) if you haven’t seen them. You can also follow the full programme here: 11+ Learning Journey.

If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected]. Thank you for being part of our journey it’s been a privilege to support your family’s learning.

*If you need to reset your password, it will still work as usual. Please check your spam folder if the reset email doesn’t appear in your inbox.

Teaching kids about current affairs

Knowing how and when to introduce children to current affairs has always been a thorny topic for parents.

When we were kids, we lost sleep over the threat of nuclear war and the hole in the ozone layer; today, children are more likely to be worried about Covid 19, terrorism and knife crime.

But while our instinct may be to protect our kids from what’s going on in the world, it’s our responsibility, just as much as their school’s, to help them make sense of the news.

Why current affairs matter to kids

Children are naturally curious, and they want to know about what’s happening in the world around them.

Indeed, this inquisitiveness is an asset, and something we should encourage, says Karthik Krishnan, global CEO of Encyclopaedia Britannica.

‘Curiosity drives learning,’ he explains. ‘One of the most important habits for children is the impulse to wonder, to question, and to ask, “Is this information I’m seeing reliable? Should I trust it?”’

Boost your child's maths & English skills!

- Follow a weekly programme

- Maths & English resources

- Keeps your child's learning on track

We’ve all hastily switched off the car radio when something unsavoury comes on the news, but it’s naïve to think that we can protect our children from finding out what’s going on in society.

‘Children are more aware than ever before about what’s happening, not just in their local community, but all around the world,’ says Katie Harrison, an Early Years educational expert and founder of Picture News: a new service helping schools teach children about the news.

‘Technology and social media mean that conversations are happening online and in the playground that wouldn’t have happened 10 years ago.’

Trying to protect our children from potentially distressing news may seem the right thing to do, but actually, creating a ‘hush hush’ atmosphere around current affairs could do more harm than good.

Overhearing – and potentially misunderstanding – information about worrying events in the playground, or even being told about them during class time or assembly, can leave children fretting if they don’t have the opportunity to talk it over.

On the contrary, fostering openness around current affairs means you can talk things over with your child, allay their fears and help them put worries into context.

‘Schools and parents need to create a culture of news talk, which can help children consider different perspectives and see the world in a more realistic light,’ Kate says.

Discussing the news with your child not only helps them share their thoughts and feelings, but also encourages them to develop empathy with others.

In addition, it prompts them to become responsible citizens. For example, a group of children in Scotland are on a mission to get plastic straws banned in the light of news stories about the global environmental crisis caused by disposable plastics.

Age-appropriate news: the right info at the right time

We’d all love to know exactly when is the right time to introduce our children to current affairs, but there’s no one-size-fits-all approach, and your instincts as a parent are likely to tell you what your child is ready for, and when.

‘There’s no official age where children are suddenly mature enough to cope with current affairs content,’ says Kate. ‘It’s more about opening the dialogue about what’s happening, providing short discussions, and answering their questions in an age-appropriate way.

‘It’s important that as adults, we don’t assume that everything in the news is out of bounds.’

9 top tips for helping your child understand current affairs

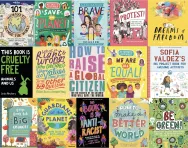

1. Look for child-friendly news sources. There are some great current affairs newspapers and magazines aimed at primary school children, including The Week Junior and First News. CBBC’s Newsround is a perennial favourite, and is also online and has its own Newsround YouTube channel.

2. Watch or read together. This allows you to answer your child’s questions as they arise. ‘Children are inquisitive, and there’s a lot that can be learned from current affairs,’ says Katie. ‘It’s a good chance to learn and find out answers together.’

3. Do your own research. If you can’t answer your child’s questions, don’t just brush them off: explain honestly that you don’t know the answer, and tell them you’ll look it up together.

4. Help your child develop research skills. ‘Children of today do most of their information gathering from digital sources,’ says Karthik. ‘Digital databases can be revised and updated continuously; they can incorporate multimedia and other non-text elements; they’re searchable in more ways than print; and they can go into greater depth because they don’t have the space limitations of print.’

5. Pick the right time to talk. ‘If you and your child need to discuss difficult news, the morning is usually the best time as they can have the day to reflect, digest and discuss it with others, and it can help prevent them worrying on their own while they’re trying to go to sleep,’ Katie explains.

6. Don’t minimise distressing topics. If your child has been upset by something they’ve heard in the news, it may be tempting to gloss over it or infer it didn’t happen, but it’s important to tell the truth. ‘The truth will usually surface, and not confronting it can lead to mistrust,’ says Katie. ‘It can be difficult to tackle issues that the world hasn’t been able to solve, but by providing children with knowledge, compassion and strong character, we can help give them some of the tools they need for understanding and empathy.’

7. Look for the helpers. In any distressing event, whether local or global, there are always people helping. Encouraging your child to look for the people who are in the midst of the situation trying to do good will help them to see the positives in every story.

8. Keep abreast of what’s happening at school. ‘In the past, we’ve heard from parents who are concerned that schools have played a news clip in haste or briefly mentioned a story without explanation,’ Katie explains. Be prepared to talk to your child about issues that have arisen at school. If they’ve been upset by something they’ve heard – often because it hasn’t been explained properly – a quiet word with the teacher may help them understand the need for clarification in future.

9. Find ways to help. If your child is distressed about something they’ve heard in the news, channeling it into action often helps. Could they launch a campaign to reduce lunchbox waste at school, or do a sponsored event to raise money for children affected by a natural disaster?

Spotting fake news

Fake news is a growing problem in this world of diverse media sources, and it can be hard for us as adults to sort fact from fiction, let alone our children.

However, it’s our job to help our kids develop the skills they need to tell real news from fake.

‘For young children, who aren’t yet highly discerning about the information they consume, it’s important for adults to play an active role in filtering sources and their content, to present them with information that is known to be reliable and safe,’ says Karthik. ‘This includes well-edited online databases, books from reputable publishers, and age-appropriate multimedia.

‘Older children who are able to start scrutinising information themselves should gradually be taught to look critically at the information they find, and be made aware that in an online world where anyone can post or publish anything they want, there will always be a lot of false, misleading, or just plain sloppy content.’

YouTube in particular can be a source of misinformation, thanks to users uploading misleading videos, so the website has teamed up with Britannica to fight conspiracy theories and provide easier access to balanced and accurate content.

There’s also a new Demystified channel, giving fact-checked answers to some of life’s great mysteries.

As with most areas of learning, our children rely on us to help them master the techniques they need to sort fake news from real. ‘It’s important that children ask open-ended questions, don’t make assumptions, and consider things with a critical eye,’ Katie explains.

‘Regularly asking, “why?” is a simple and effective strategy: “Why is this being talked about? Why is it on social media/in my classroom?” This way, they are not looking at a news article purely as a piece of information, but viewing it from an informed and inquiring perspective.’